Conditional Random Fields (CRFs)

Table of Contents

Overview

- Graphical model

- Is a discriminative model => attempts to directly model

Graphical models

Distributions over very many variables can often be represented as a product of local functions that depend on a much smaller subset of variables.

Undirected models

Notation

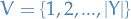

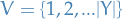

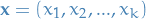

is a set of rvs. that we target

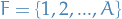

is a set of rvs. that we target takes outcomes from the (continuous or discrete) set

takes outcomes from the (continuous or discrete) set

is an arbitrary assignment to

is an arbitrary assignment to

denotes value assigned to

denotes value assigned to  by

by

is summation over all possible combinations of

is summation over all possible combinations of  where

where

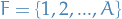

is factor where

is factor where  is an index in

is an index in  ,

,  being the number of factors

being the number of factors is a indicator variable, having value

is a indicator variable, having value  if

if  and

and  otherwise

otherwise for some rvs.

for some rvs.  denotes the neighbors of

denotes the neighbors of  in some graph

in some graph

usually denotes indices for rvs. of some graph

usually denotes indices for rvs. of some graph

usually denotes the indices for factors of some graph

usually denotes the indices for factors of some graph

Factors

- Believe probability distribution

can be represented as a product of

factors

can be represented as a product of

factors

- Each factor

depends only on a subset

depends only on a subset  of the variables

of the variables - Non-negative scalar which can be thought of a compatibility measure between

the values

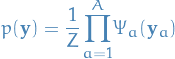

Formally, given a collections of subs  of

of  , an unidirected graphical model

is the set of all distributions that can be written as

, an unidirected graphical model

is the set of all distributions that can be written as

1

1

for any choice of factors  that have

that have  for all

for all  .

.

We use the term random field to refer to a particular distribution among those defined by a unidirected graphical model.

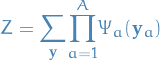

The constant  is the normalization factor (also referred to as the

parition function) that ensures the distribution

is the normalization factor (also referred to as the

parition function) that ensures the distribution  sums to

sums to  .

.

2

2

Notice that the summation in  is over the exponentially many possible assignments

is over the exponentially many possible assignments  .

.

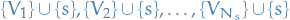

Factor graph

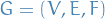

A factor graph is biparite graph  , i.e. a graph with

two disjoint sets of nodes

, i.e. a graph with

two disjoint sets of nodes  and

and  :

:

indexes the rvs. in the model

indexes the rvs. in the model indexes the factors

indexes the factors

By this representation, we mean that if a variable node  for

for  is connected to a

factor node

is connected to a

factor node  for

for  then

then  is one of the arguments of

is one of the arguments of  .

.

Markov network

A Markov network represents the conditional independence relationships

in a multivariate distribution, and is a graph over random variables only.

That is;  is a graph over integers (rv. indices)

is a graph over integers (rv. indices)  .

.

A distribution  is Markov with respect to

is Markov with respect to  if it satisfies the local

Markov property: for any two variables

if it satisfies the local

Markov property: for any two variables  , the variable

, the variable  is independent of

is independent of  conditioned on its neighbors,

conditioned on its neighbors,  . Intuitively,

this means that

. Intuitively,

this means that  contains all the information that is useful for

predicting

contains all the information that is useful for

predicting

An issue with a Markov network is that it is ambigious, i.e. "not descriptive enough" from the factorization persepective. If you have a look at the figure below you can see an example of what we're talking about.

Any distribution that factorizes as  for some

positive function

for some

positive function  is Markov with respect to this graph. However, we

might want to represent the graph using a more restricted parameterization,

where

is Markov with respect to this graph. However, we

might want to represent the graph using a more restricted parameterization,

where  . This is a more strict

family of functions, and so one would expect it to be easier to estimate.

Unfortunately, as we can see in the figure, Markov networks doesn't really

distinguish between these cases. Lucky us, factor graphs do!

. This is a more strict

family of functions, and so one would expect it to be easier to estimate.

Unfortunately, as we can see in the figure, Markov networks doesn't really

distinguish between these cases. Lucky us, factor graphs do!

Directed Models

- Describes how the distribution factorizes into a local conditional probability distribution.

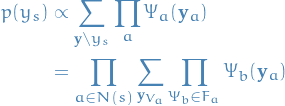

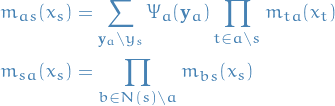

Inference

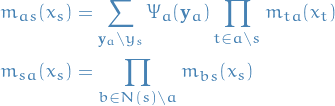

Belief propagation

Notation

is the variable we want to compute the marginal distribution for

is the variable we want to compute the marginal distribution for is the neighborhood of *factors of

is the neighborhood of *factors of  , and it's the index of the neighboring factor of

, and it's the index of the neighboring factor of

the set of variables "upstream" of

the set of variables "upstream" of  , i.e. set of variables

, i.e. set of variables  for which the factor

for which the factor  is between

is between  and

and  (

( separates

separates  and

and  ), with

), with  being the index of a neighboring factor of

being the index of a neighboring factor of

the set of factors "upstream" of

the set of factors "upstream" of  , i.e. set of factors for which

, i.e. set of factors for which  is between those and

is between those and  ("separates"

("separates"  from this set of factors), including the factor

from this set of factors), including the factor  itself

itselfMessage from

to

to

Stuff

- Direct generalization of exact algorithms for Linear CRFs (i.e. Viterbi algorithm for sequences and Forward-backward algorithm for joint distributions)

- Each neighboring factor of

makes a multiplicative contribution to the marginal of

makes a multiplicative contribution to the marginal of  , called a message

, called a message

In the special case where our graph is a tree, the graph itself is a the one and only spanning tree, hence we partition the entire graph wrt.  : the sets

: the sets  form a partition of the variables in

form a partition of the variables in  . In a bit simpler wording:

. In a bit simpler wording:

- You're looking at

- Choose some other variable (node in the graph)

- All variables between

and

and  are along a single path (i.e. only one possible way to traverse from

are along a single path (i.e. only one possible way to traverse from  to

to  )

) - Therefore, the sets

form a partition of the variables in

form a partition of the variables in  , where

, where  denotes the number of neighboring nodes of

denotes the number of neighboring nodes of

- Thus, we can split upt the summation required for the marginal into a product of independent subproblems

And denoting each of the factors in the above equation by  , i.e.,

, i.e.,

which can be though of as a message from  to

to  .

.

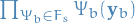

And also, if instead take the product over neighboring factors, we can define the message from variables to factors as

which would give us

Let's break this down:

is product over all variables

is product over all variables  which are neighbors to the factor

which are neighbors to the factor

are all possible values the variables

are all possible values the variables  (i.e. "variables on one side of

(i.e. "variables on one side of  , including

, including  ") can take on

") can take on is the product over all neigboring factors

is the product over all neigboring factors  of the variable

of the variable  , excluding

, excluding  itself (which is our "focus" at the moment)

itself (which is our "focus" at the moment)

Observe that when talking about the "marginal for a factor ", we're looking at the marginal of a vector  rather than a single value

rather than a single value  as in the marginal for a variable.

as in the marginal for a variable.

denotes the vector of random variables

denotes the vector of random variables  with

with  which are incoming to

which are incoming to  , NOT the distribution over the output of

, NOT the distribution over the output of

Luckily, we can rewrite the messages recursively

These recursion-relations define the belief propagation algorithm.

Belief progagation is the algorithm defined by the following recursion relations:

In the case where the graph  is not a tree, we do not have the guarantee of convergence and refer to this algorithm as loopy belief propagation, as we can still find a fixed point.

is not a tree, we do not have the guarantee of convergence and refer to this algorithm as loopy belief propagation, as we can still find a fixed point.

As it turns out, Loopy BP can in fact be seen as a variational method, meaning that there actually exists an objective function over beliefs that is approximately minimized by the iterative BP procedure.

Appendix A: Vocabular

- random field

- a particular distribution among those defined by an unidirected graphical model

- biparite graph

- set of graph vertices decomposed into two disjoint sets s.t. no two graph vertices from the same set are adjacent / "directly connected".

- markov blanket

- simply a fancy word for the independent neighbors

- multivariate distribution

- distribution of multiple variables

Appendix B: Discriminative vs. Generative methods

- Discriminative model

- attempts to model

, and thus indirectly model

, and thus indirectly model  using Bayes'

using Bayes' - Generative model

- attemps to model

directly

directly

First, it's very hard (impossible?) to tell beforehand whether a generative or discriminative model will perform better on a given dataset. Nonetheless, there are some benefits/negatives to both.

Benefits of discriminative:

- Agnostic about the form of

- Make independence assumptions among

and how

and how  depend on

depend on  , but

do not make conditional independence assumptions between the $$s

, but

do not make conditional independence assumptions between the $$s - Thus, these models are better at suited for including rich, overlapping (dependent) features.

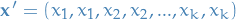

- Better probability estimates than generative models; consider a vector of features

which we transform to repeat the features, like so

which we transform to repeat the features, like so  .

Then train, say a Naive Bayes', on this data. Even though no new data has been added

(just added multiple completely correlated features), the model will be more confident

in the probability estimates, i.e.

.

Then train, say a Naive Bayes', on this data. Even though no new data has been added

(just added multiple completely correlated features), the model will be more confident

in the probability estimates, i.e.  will be further away from

will be further away from  than

than  .

Note that his in a way demonstrates the independence assumption between the features which

is beeing made a generative model.

.

Note that his in a way demonstrates the independence assumption between the features which

is beeing made a generative model.

Benefits of generative model:

- More natural for handling latent variables, partially-labeled data, and unlabeled data. Even in extreme case of unlabeled data, generative models can be applied, while discriminative methods is less natural.

- In some cases, generative model can perform better, intuitively because

might have a smoothening effect on the conditional.

might have a smoothening effect on the conditional. - If application of the model requires both prediction of future inputs as well as outputs, generative models is a good choice since they model the joint distribution, and so we can potentially marginalize over whatever we don't want to predict to obtain a prediction for our target variable (being input or output).

It may not be clear why these approaches are different, as you could convert from one to the other, both ways, using Bayes' rule.

TODO Ongoing work

One interesting way to look at it is as follows:

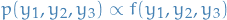

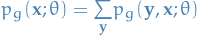

Suppose we have a generative model  which takes the form:

which takes the form:

3

3

And using the chain rule of probability we get

4

4

where:

is computed by inference

is computed by inference is computed by inference

is computed by inference

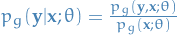

And then suppose we another model, but this is discriminative model  :

:

Resources

Named Entity Recognition with a Maximum Entropy Approach A paper using MEMMs for word-tagging. I link this here since MEMMs are very similar to CRFs, but also because they provide a very nice set of features for use in word-tagging, which is something you might want to use CRFs for.

In fact, both CRFs and MEMMs are discriminative, unlike the generative HMMs, sequence models. Both CRFs and MEMMs are MaxEnt (maximum entropy) models, but a CRF is models the entire sequence while MEMMs makes decisions for each state independently of the other states.