Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning

Table of Contents

Introduction

Gaussian processes is a generalization of Gaussian probability distribution to continuous case where we deal with these infinite number of functions by only considering a finite number of points.

Two common appraoches to deal with supervised learning:

- Restrict the class of functions that we consider

- Prior probability to every possible function

- How do we compare a infinite number of functions?

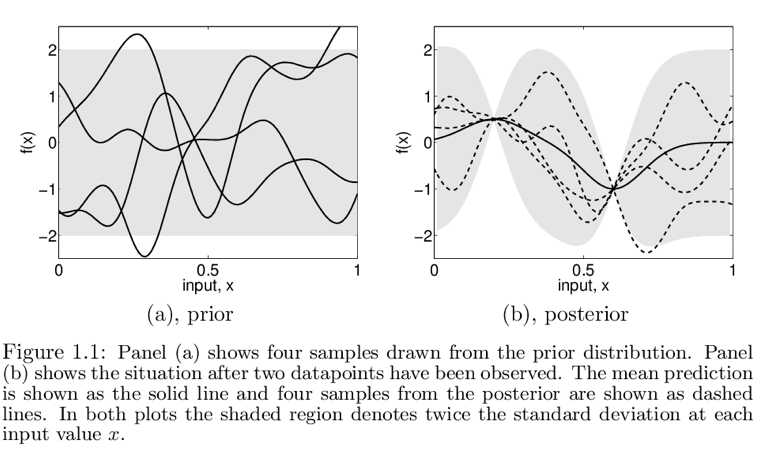

A Pictorial Introduction to Bayesian Modelling

1D regression

- Here we specify a prior over functions specified by a particular Gaussian process which favours smooth functions

- We assume a 0 mean for every

x, since we don't have any prior knowledge - We then add two data points

and only consider functions passing through these two points,

ending up with the posterior in 1.1 b

and only consider functions passing through these two points,

ending up with the posterior in 1.1 b

Figure 1: From rasmussen2006gaussian

Regression

There are multiple ways to interpret a Gaussian process (GP)

Weight-space view

Notation

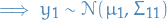

is

is  of

of  observations

observations = input vector of dimension

= input vector of dimension

= scalar output/target

= scalar output/target =

=  design matrix with all

design matrix with all  input vectors

as column vectors

input vectors

as column vectors

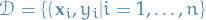

Standard Linear Model

Bayesian analysis of the standard linear regression model with Gaussian noise:

1

1

- Often a bias is included, but this can easily be implemented by adding

a extra element to the input vector

, whose value is always

, whose value is always

- The noise assumption (

to be normally distributed) together

with the model direcly gives us the likelihood, ergo the probability

density of the observations given the parameters.

to be normally distributed) together

with the model direcly gives us the likelihood, ergo the probability

density of the observations given the parameters.

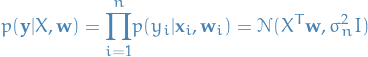

Because of (assumed) independence between samples:

2

2

In the Bayesian formalism we need to specify a prior over the parameters,

expressing our beliefs about the parameters before considering the observations.

We simply give a zero mean Gaussian with covariance matrix  on the weights

on the weights

3

3

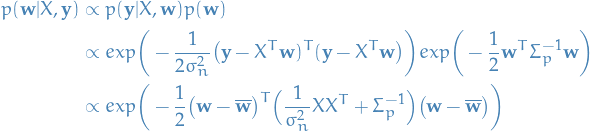

Inference in a Bayesian linear model is based on the posterior distribution over the weights:

4

4

where the normalization constant or marginal likelihood is given by

5

5

If we can obtain  without explicitly calculating this integral,

this is what they call "integrating out the weights".

without explicitly calculating this integral,

this is what they call "integrating out the weights".

For now we ignore the marginal distribution in the denominator, and then we have

6

6

where  .

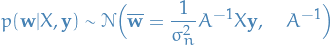

Notice how this has the form of a Gaussian posterior with mean

.

Notice how this has the form of a Gaussian posterior with mean  and covariance matrix

and covariance matrix  :

:

7

7

where  .

.

I suppose this is legit without having to compute the marginal likelihood since we can easily obtain the normalization constant for a Gaussian Distribution.

For this model, and indeed for any Guassian posterior, the mean

of the posterior  is also its mode,

which is also called the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate of

is also its mode,

which is also called the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate of  .

.

The meaning of the log prior and the MAP estimate substantially differs between Bayesian and non-Bayesian settings:

- Bayesian

MAP estimate plays no special role

MAP estimate plays no special role - Non-Bayesian

negative prior is sometimes used as penalty term, and

MAP point is known as the penalized maxium likelihood estimate

of the weights. In fact, this is what is known as ridge regression,

because of the quadratic term

negative prior is sometimes used as penalty term, and

MAP point is known as the penalized maxium likelihood estimate

of the weights. In fact, this is what is known as ridge regression,

because of the quadratic term  from the log prior.

from the log prior.

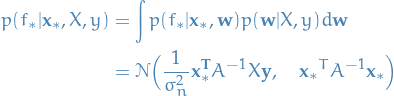

To make predictions for some input  , we average over all the

parameter values, weighted by their posterior probability. Thus the

predictive distribution for

, we average over all the

parameter values, weighted by their posterior probability. Thus the

predictive distribution for  , is given by

averaging (or rather, taking the expectation for

, is given by

averaging (or rather, taking the expectation for  over the

weights

over the

weights  ) the output of all possible linear models w.r.t. the

Gaussian posterior

) the output of all possible linear models w.r.t. the

Gaussian posterior

8

8

And even the predictive distribution is Gaussian! With a mean given by the posterior mean of the weights from eq. (2.8) multiplied by the new input. All hail Gauss!

The above step demonstrates a crucial part: we can consider all possible weights simply by "integrating out" or "marginalizing over" the weights.

Also note how the predictive variance is a quadratic of the new input, and so the prediction will be more uncertain as the magnitude of test input grows.

Projections of Inputs into Feature Space

- Can overcome linearity by projecting features into higher-dimensional space allowing us to implement polynomial regression

- If projections are independent of parameters

=> model is still linear in the parameters

and therefore analytically solvable/tractable!

=> model is still linear in the parameters

and therefore analytically solvable/tractable! - Data which is not linearly separable in the original data space may become linearly separable in a high dimensional feature space.

Function-space view

Our other approach is to consider inference directly in the function space, i.e. use a GP to describe a distribution over functions.

A Gaussian process is a collection of random variables, any finite number of which have a joint Gaussian distribution.

A GP is completely specified by its mean function  and

covariance function

and

covariance function  . For a real process

. For a real process

![\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

m(\mathbf{x}) &= E[f(\mathbf{x})] \\

k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x'}) &= E[(f(\mathbf{x}) - m (\mathbf{x}))(f(\mathbf{x'}) - m (\mathbf{x'}))] \\

\end{split}

\end{equation*}](../../assets/latex/gaussian_processes_for_machine_learning_6dbcaf36bb18e84b65c93907c885cb64841618f2.png) 9

9

and we write the Gaussian process as

10

10

Usually, for notational simplicity we will take  ,

though this need-not be done.

,

though this need-not be done.

Consistency requirement / marginalization property

GP is defined as collection of rvs  a consistency requirement.

This simply means that if the GP e.g. specifies

a consistency requirement.

This simply means that if the GP e.g. specifies  ,

,

The defintion does not exclude GPs with finite index sets (which would just be Gaussian distributions).

Simple example

Example of GP can be obtained from our Bayesian linear regression model  with prior

with prior  .

.

![\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

E[f(\mathbf{x})] &= \psi(\mathbf{x})^T E[\mathbf{w}] = 0 \\

E[f(\mathbf{x}) f(\mathbf{x'})] &= \psi(\mathbf{x})^T E[\mathbf{w} \mathbf{w}^T] \psi(\mathbf{x'})

= \psi(\mathbf{x})^T \Sigma_p \psi(\mathbf{x'})

\end{split}

\end{equation*}](../../assets/latex/gaussian_processes_for_machine_learning_c270b9b03b787a3d135b4e90408a19bc7c846472.png) 11

11

Ergo,  and

and  are jointly Gaussian with zero mean

and covariance given by

are jointly Gaussian with zero mean

and covariance given by  .

.

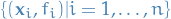

Predictions using noise-free observations

- We know

= vector of training outputs

= vector of training outputs = vector of test outputs

= vector of test outputs- Join distribution of training and test outputs according to the prior is then

12

12

- If

training points and

training points and  test points, the matrix

test points, the matrix

= covariaces evaluated at all pairs of training

and test points, and similarily for

= covariaces evaluated at all pairs of training

and test points, and similarily for  , etc.

, etc. - Restrict this joint prior distribution to contain only

those functions which agree with the observed data points

- A lot of functions mate

not efficient

not efficient In probabilistic terms this operation is simple: equivalent of conditioning on the joint Gaussian prior distribution on the observations to give

13

13

- A lot of functions mate

- Now we can sample values for

(corresponding

to test inputs

(corresponding

to test inputs  ) from the joint posterior distribution

by evaluating the mean and covariance matrix from the eqn. above.

) from the joint posterior distribution

by evaluating the mean and covariance matrix from the eqn. above.

Appendix A: Stuff to know

Sampling from a Multivariate Gaussian

Assuming we have access to a Gaussian scalar generator.

Want samples  with arbitrary mean

with arbitrary mean  and covariance

and covariance  .

.

- Compute Cholesky decomposition (also known as "matrix square

root")

of the positive (semi? not sure) definite symmetric

covariance matrix

of the positive (semi? not sure) definite symmetric

covariance matrix

is lower triangular matrix

is lower triangular matrix

- Generate

by

multiple separate calls to the scalar Gaussian generator

by

multiple separate calls to the scalar Gaussian generator - Compute

- Has desired distribution with mean

and covariance

and covariance

![$L E[\mathbf{u}\mathbf{u}^T] L^T = LL^T = K$](../../assets/latex/gaussian_processes_for_machine_learning_395eba8336fdd19c8616bbbc9e617100b9536ec6.png) , by

independence of

, by

independence of

- Has desired distribution with mean

Cholesky Decomposition

Decomposes a symmetric, positive definite matrix

into

a product of a lower triangular matrix

into

a product of a lower triangular matrix  and its transpose:

and its transpose:

14

14

- Useful for solving linear systems with symmetric, positive

definite coefficient matrix

.

.

- Want to solve

for

for

- Solve the triangular system

by forward substitution

by forward substitution - Solve triangular system

by backward substition

by backward substition - Solution is

= vector

= vector  which solves

which solves

- Want to solve

Complexity

- Both forward and backward substitution requires

operations, when

operations, when  is of size

is of size  .

. - The computation of the Cholesky factor

is considered

numerically extremely stable and takes time

is considered

numerically extremely stable and takes time  .

.

Forward/backward substitution

For a lower triangular matrix we can write  as follows

as follows

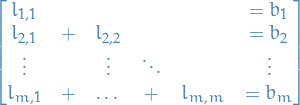

15

15

Notice that  , and so we can solve

, and so we can solve  by substituting

by substituting  in, i.e. forward substitution.

in, i.e. forward substitution.

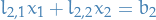

Doing this repeatedly leads to the full solution for  , that is:

, that is:

16

16

For backward substitution we do the exact same thing, just in reverse, since we're then dealing with a upper triangular matrix.

Appendix B: Derivations

Kernel

Declarations

= input space

= input space = feature space

= feature space

= matrix with columns

= matrix with columns  for all training inputs

for all training inputs

Model

17

17

where  is of length

is of length  . This is analogous to the standard linear model

except everywhere

. This is analogous to the standard linear model

except everywhere  is substituted for

is substituted for  .

.

Appendix C: Exercises

Chapter 2: Regression

Ex. 1

First we import the stuff that needs to be imported

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

from __future__ import division

After having some issues, I found this article from which I used some of the code, so thanks a lot to Chris Fonnesbeck!

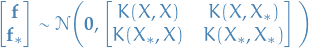

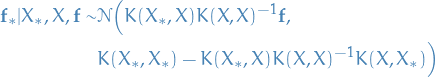

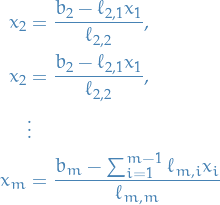

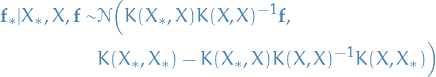

We start out by the following specification for our Gaussian Process:

18

18

def exponential_cov(x, y, theta):

return theta[0] * np.exp(-0.5 * theta[1] * np.subtract.outer(x, y) ** 2)

Then to compute the conditional probability for some new input  conditioned on the previously send

inputs with outputs, we use the following:

conditioned on the previously send

inputs with outputs, we use the following:

19

19

where, again, remember that  and

and  represents the test and training outputs, i.e in the case of

training (already seen) inputs:

represents the test and training outputs, i.e in the case of

training (already seen) inputs:

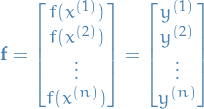

20

20

def conditional(X_star, X, y, theta):

B = exponential_cov(X_star, X, theta)

C = exponential_cov(X, X, theta)

A = exponential_cov(X_star, X_star, theta)

mu = np.linalg.inv(C).dot(B.T).T.dot(y)

sigma = A - B.dot(np.linalg.inv(C).dot(B.T))

return mu.squeeze(), sigma.squeeze() # simply unwraps any 1-D arrays, so (1, 100) => (100,)

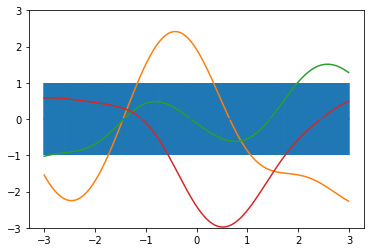

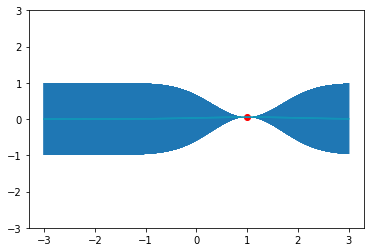

For now we set  :

:

theta = (1, 1)

sigma_theta = exponential_cov(0, 0, theta)

xpts = np.arange(-3, 3, step=0.01)

plt.errorbar(xpts, np.zeros(len(xpts)), yerr=sigma_theta, capsize=0)

plt.ylim(-3, 3)

# some sampled priors

f1_prior = np.random.multivariate_normal(np.zeros(len(xpts)), exponential_cov(xpts, xpts, theta))

f2_prior = np.random.multivariate_normal(np.zeros(len(xpts)), exponential_cov(xpts, xpts, theta))

f3_prior = np.random.multivariate_normal(np.zeros(len(xpts)), exponential_cov(xpts, xpts, theta))

plt.plot(xpts, f1_prior)

plt.plot(xpts, f2_prior)

plt.plot(xpts, f3_prior)

We select an arbitrary starting point, say  , and simply sample from a normal distribution

with unit covariance. This is just for us to have a "seen" sample to play with.

, and simply sample from a normal distribution

with unit covariance. This is just for us to have a "seen" sample to play with.

x = [1.] y = [np.random.normal(scale=sigma_theta)] np.array(y)

We now update our confidence band, given the point we just sampled,

by using the covariance function to generate new point-wise confidence intervals,

conditional on the value  seen above.

seen above.

At a first glance it might look like conditional and predict_noiseless are the same functions,

but the difference is that predict_noiseless returns the mean and (noiseless) variance at each point

where as conditional returns the mean and the entire covariance matrix for all the test points.

So if you want to draw function samples (as we do later on), you'll want to use the conditional, while

if you're simply after the mean-line and it's uncertainty at each evaluated point you use the predict_noiseless.

sigma_1 = exponential_cov(x, x, theta) # compute covariance for new point

def predict_noiseless(x, data, kernel, theta, sigma, f):

K = [kernel(x, y, theta) for y in data] # covariance between test input and training input

sigma_inv = np.linalg.inv(sigma) # inverting the covariance matrix for training input

K_dot_sigma_inv = np.dot(K, sigma_inv)

y_pred = K_dot_sigma_inv.dot(f) # compute the predicted mean

sigma_new = kernel(x, x, theta) - K_dot_sigma_inv.dot(K) # covariance of new point

return y_pred, sigma_new

x_pred = np.linspace(-3, 3, 2000)

predictions = [predict_noiseless(i, x, exponential_cov, theta, sigma_1, y) for i in x_pred]

y_pred, sigmas = np.transpose(predictions) plt.errorbar(x_pred, y_pred, yerr=sigmas, capsize=0, alpha=0.6) plt.plot(x, y, "ro") plt.plot(x_pred, y_pred, c="c") plt.ylim(-3, 3)

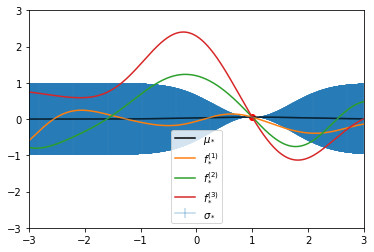

Notice that here we are predicting a mean  and covariance

and covariance  at each test point,

but for fun's sake we can sample some functions too!

at each test point,

but for fun's sake we can sample some functions too!

21

21

That is; we create a normal distribution of dimension equal to the number of test inputs,

draw from this distribution, then the sample at index i corresponds to  , yah see?

It's weird, yes, but allows the indexed sample points to be any real value!

, yah see?

It's weird, yes, but allows the indexed sample points to be any real value!

# same as above

plt.errorbar(x_pred, y_pred, yerr=sigmas, capsize=0, alpha=0.3, label="$\sigma_*$")

plt.plot(x, y, "ro")

plt.plot(x_pred, y_pred, c="black", label="$\mu_*$")

plt.ylim(-3, 3)

plt.xlim(-3, 3)

# Some sampled functions

mu_star, K_star = conditional(x_pred, x, y, theta) # x_pred conditioned on training input (x, y)

f1 = np.random.multivariate_normal(mu_star, K_star)

f2 = np.random.multivariate_normal(mu_star, K_star)

f3 = np.random.multivariate_normal(mu_star, K_star)

plt.plot(x_pred, f1, label="$f_*^{(1)}$")

plt.plot(x_pred, f2, label="$f_*^{(2)}$")

plt.plot(x_pred, f3, label="$f_*^{(3)}$")

plt.legend()

Issues

I had multiple issues with following the book:

- Covariance matrix of the input matrix that I come up with

is not positive definite => can't use Cholesky decomposition

to draw samples, nor to circumvent having to compute the inverse.

There is no guarantee for this to be the case either, but there is a

guarantee that for a real matrix we will have a semi-positive definite

covariance matrix, which allows for drawing from a Gaussian by basically

replacing each L step with the equivalent SVD step (where we use the

product

instead of

instead of  ).

). - What to transpose and so on in the computation of the mean vector and covariance matrix for the predictions I got wrong multiple times… IT'S HARD, MKAY?!

Some of my own deprecated / horrible work

To generate samples  with arbitrary

mean

with arbitrary

mean  and covariance matrix

and covariance matrix  using a scalar Gaussian generator,

we proceed as follows:

using a scalar Gaussian generator,

we proceed as follows:

- Compute the Cholesky decomposition (also known as the "matrix square root")

of the

positive-definite symmetric covariance matrix

of the

positive-definite symmetric covariance matrix  , where

, where  is lower triangular.

is lower triangular. - Generate

by multiple separate calls to the scalar Gaussian generator.

by multiple separate calls to the scalar Gaussian generator. - Compute

, which has the desired distribution with:

, which has the desired distribution with:

- Mean

- Cov.

![$L \mathcal(E)[\mathbf{u}\mathbf{u}^T] L^T = LL^T = K$](../../assets/latex/gaussian_processes_for_machine_learning_c100167709245a0e426742f1336da32d40343e04.png) (by independence of the elements of

(by independence of the elements of  )

)

- Mean

def gaussian_draws(m, K, N=10000):

"""

IMPORTANT: This version uses the Cholesky decomposition which ONLY works if the

matrix `X` is positive definite symmetric, which is often not the case! A covariance

matrix is only guaranteed to be SEMI-positive definite symmetric.

"""

dim = m.shape[0]

X = np.zeros((N, dim))

L = np.linalg.cholesky(K)

for i in range(N):

u = np.random.normal(0, 1, dim)

X[i, :] = m + np.dot(L, u)

if N == 1:

return X[0] # return a single vector if only 1 sample is requested

else:

return X

m = np.array([2, 1, 0])

K = np.array([[2, -1, 0], [-1, 2, -1], [0, -1, 2]]) # this is positive-definite

X = gaussian_draws(m, K, 10)

X

Of course I could just have take advantage of the fact that numpy can generate the

entire sample-matrix for me, buuut I dunno, felt like doing some work myself, though

it's not much.

And if you want to know how we can draw from a semi-positive definite symmetric matrix, checkout this. Explains how you ought to use SVD in this case.

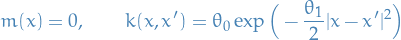

And then we need to able to compute the squared exponential kernel function:

22

22

def squared_exponential(X, l=2):

"""

DEPRECATED. Use exponential_cov instead. Much better.

Computes the squared exponential (also known as Radial Basis function) of the

the matrix `X`.

Assumes `X` to be of the shape (n, p) where n is the number of samples, and p is the

number of random variables for which we have samples.

"""

dim = X.shape[0]

K = np.zeros((dim, dim))

for p in range(dim):

x_p = X[p]

for q in range(p, dim):

x_q = X[q]

diff = np.subtract(x_p, x_q)

# since the resulting covariance matrix will be symmetric we only need to compute

# the triangular matrix, and then copy the values.

se = np.exp(- (1 / l) * (diff ** 2).sum())

K[p, q] = se

# stop us from assigning to the diagonal entries

# twice, being SLIGHTLY more performant, yey!

if p != q:

K[q, p] = se

return K

squared_exponential(np.arange(3))

Ex. 2

Bibliography

Bibliography

- [rasmussen2006gaussian] Rasmussen & Williams, Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning, MIT Press (2006).